A worker cleans the floor of a showroom during a presentation of the Union Budget 2025-26, in Mumbai, on February 1.

| Photo Credit: PTI

It would not be an exaggeration to say that this is the biggest tax cut that the middle class has ever got in any Union Budget. To be sure, the tax-paying middle class in India is nowhere near “middle” of the income spectrum and, hence, those who would directly benefit from these cuts are a minuscule minority (between 2-3% of the population). Nevertheless, it is indeed a significant cut in tax rates for every class of taxpayer. For those earning between ₹7-₹12 lakh a year, it is a complete tax rebate, which was earlier applicable to only those below ₹7 lakh. For others earning more than ₹12 lakh, the exemption limit has increased from ₹3 to ₹4 lakh. The rest of the tax slabs have also changed favourably along with a cut in the marginal tax rates. So, everyone earning more than ₹7 lakh stands to gain in taxes payable. No wonder this step, as noted by the Finance Minister, will lead to a fall in tax revenue to the tune of ₹1 lakh crore. This is 8% of the direct income tax collection of ₹12.57 lakh crore in the current year.

Also Read: Union Budget 2025: Tax break will give a fillip to slowing economy, says Centre

Budgets are an exercise in both a redistribution of income (through differential variation in tax rates) and affecting the level of economic activity through its expenditure decisions.

Since the tax rebate has implications for both, and a lot of the plans of the 2025 Budget ride on it, this piece primarily focuses on this unprecedented fall in income tax rates.

The logic behind the tax rebates

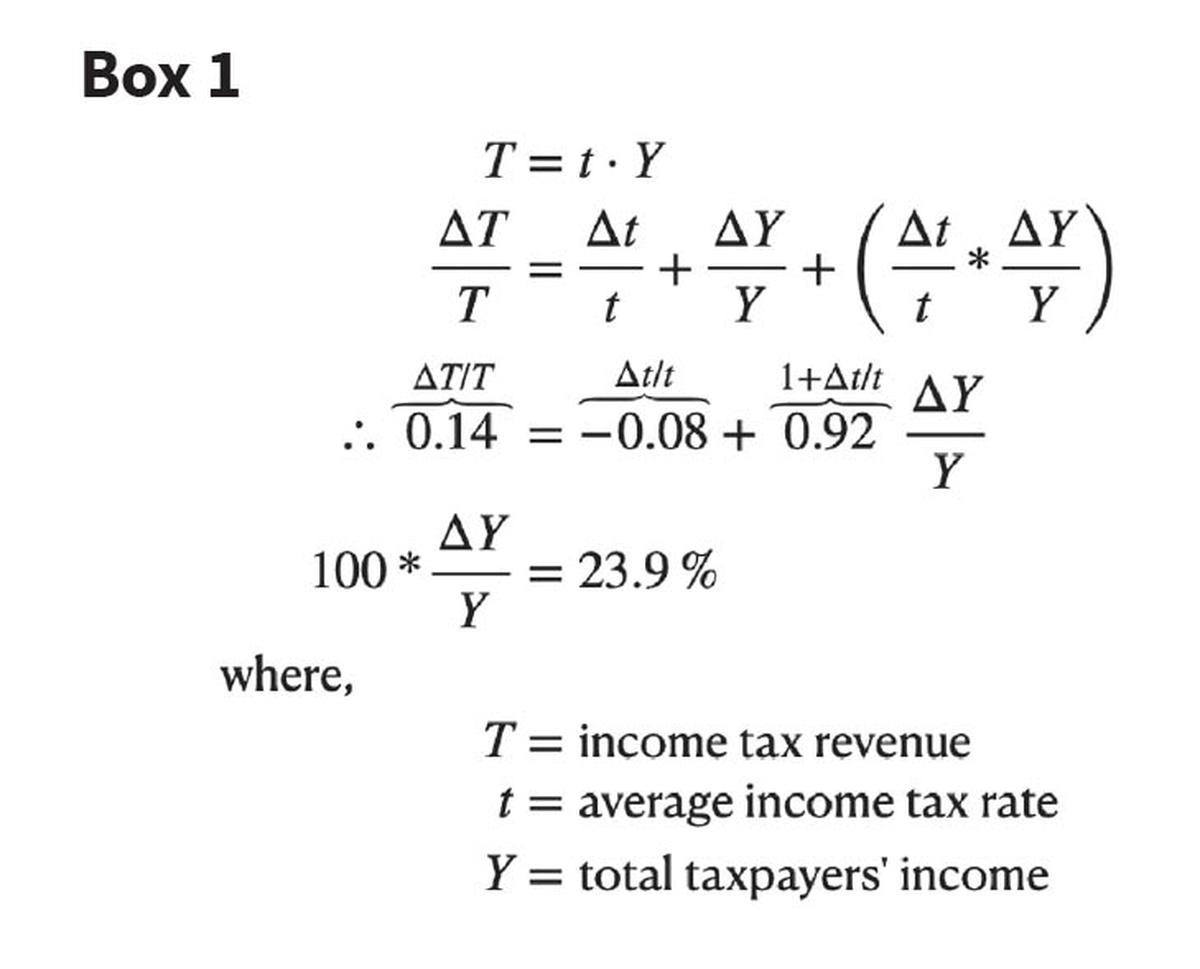

Despite the fall of 8% in the effective tax rate as a result of this policy, the Budget has estimated direct tax collection to go up by 14%. A simple arithmetic calculation would tell us that this requires the rise of income to be around 24% (see Box 1).

With a projected growth of 10.1% in nominal GDP, this means more than double the growth in taxpayers’ income. This may or may not happen. Let’s discuss each of the two scenarios.

First, the optimistic scenario. In the backdrop of higher tax exemption limits (from ₹7 to ₹12 lakh for zero tax and ₹3 to ₹4 lakh for those earning more than 12 lakh), this would require either a significant rise in the number of people earning more than ₹12 lakh and/or a significant rise in the income of the current taxpayers, that is, what economists would call higher tax buoyancy. If it’s the latter, this means further concentration of income in the hands of the upper classes. This may just further the K-shaped growth that the country has witnessed since the pandemic. And if it’s the former, this may reflect some upward mobility at the upper end of the income spectrum.

Worst-case scenario

Now, the pessimistic scenario. If the tax buoyancy does not quite work out, the implication of it is going to fall on the poor and disadvantaged of this country.

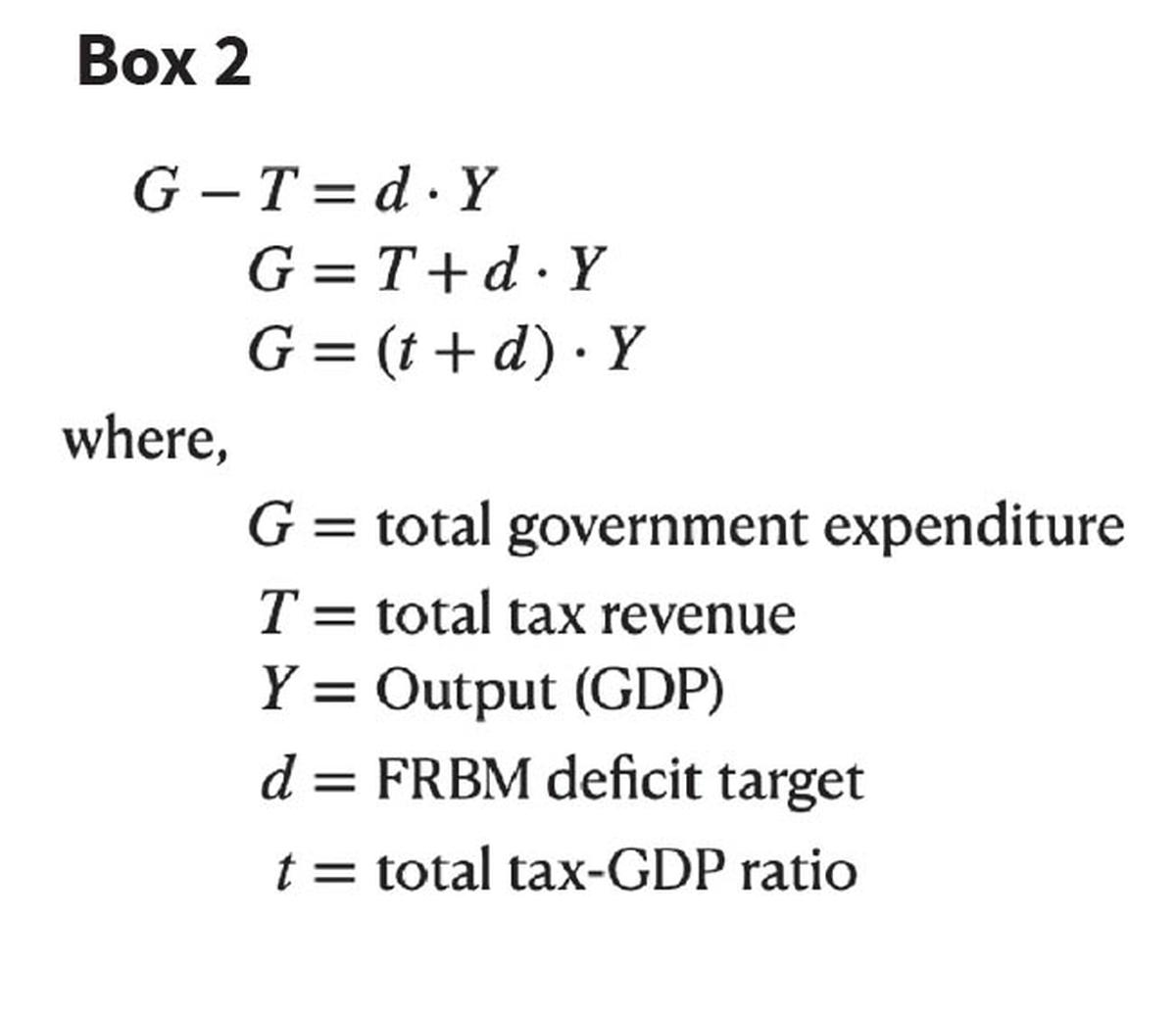

In a world where expenditure by the government is directly linked to tax revenue, any shortfall on the tax side will show up on the expenditure side as well. With the Fiscal Responsibility Budgetary Management Act (FRBM) in place, governments are bound by how much they can spend over and above their tax revenue and that deficit limit is set in the Budget every year (see Box 2).

The state effectively loses control over how much it can spend, and the fiscal policy becomes pro-cyclical (it increases or decreases with GDP) instead of countercyclical as it is supposed to be. The idea of fiscal policy arose in economics from the assumption that it could be expanded in conditions of slowdown and contracted during booms. Adherence to FRBM does the exact opposite.

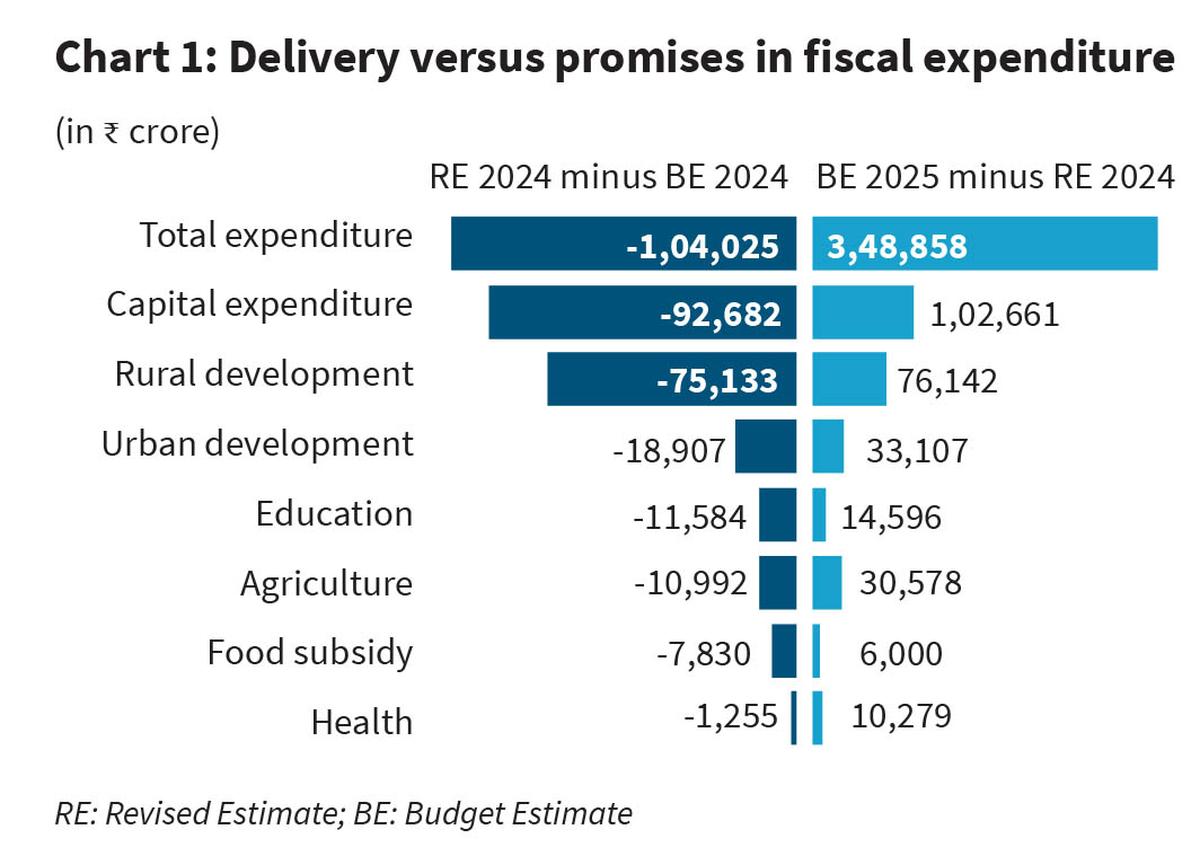

This government’s track record on strictly adhering to its deficit targets is quite telling. In a year, when the government was worried about a four-year low in economic growth, it has dared to revise its deficit target down from 5% as announced in the 2024 Budget to 4.8%. No wonder this fall in deficit has been managed through an almost across the board cut in expenditures compared to the figures announced in Budget 2024 (Chart 1 shows categories of expenses where there has been a fall). The left column in the chart shows the difference between what the Finance Minister announced last year and what the revised expenses actually were. As is evident, there has been a fall of ₹1 lakh crore in total expenditure. So, the government fell way short of its 2024 promises in terms of its commitments. The promises made in Budget 2025 (the right column of chart 1) are a significant jump from the revised figures of the last Budget. These promises can only be fulfilled if revenue plans turn out to be correct otherwise there would have to be similar (or more) cuts in the actual expenses made in 2025-26.

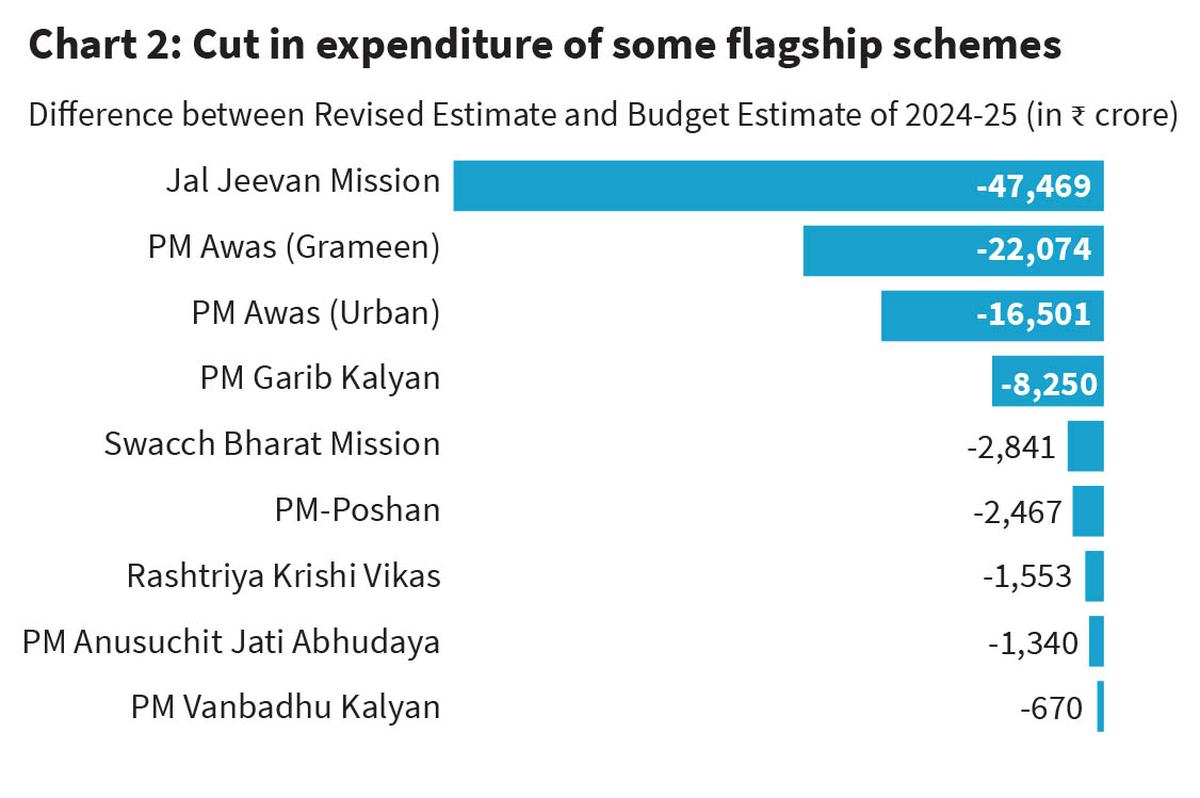

That the government is extremely serious about managing its deficit becomes clearer if one looks at some of the schemes that have been associated with the Prime Minister. Chart 2 presents the difference between the Budget and Revised Estimates for some of these important schemes. It can be seen that the cut has been across most of the flagship schemes. So, when this government promises fiscal consolidation, it really means it, no matter what the underlying economic circumstances are. The only exception to this rule is perhaps the pandemic where fiscal consolidation was paused for a brief while.

Fiscal consolidation or contraction?

What is additionally worrying on this count is that the Finance Minister has announced an even lower deficit target this Budget, down from 4.8% (RE 2024) to 4.4% (BE 2025). It’s not fiscal consolidation alone, it’s fiscal contraction. If a 4.8% couldn’t deliver a turnaround in growth, a 4.4% is less likely to. Even if you were a fiscal hawk, now is not the time to be one. With growth slowing down, the economy requires exogenous stimuli (exogenous to the current level of activity), which propels the economy. Such an exogenous stimulus usually comes from exports, corporate investment or government expenditure. With the last lever gone (as expenditure becomes pro-cyclical), the government is effectively banking on exports and corporate investment to bring about a turnaround in growth. If we go by the 2025 Economic Survey, policymakers are not very optimistic about global demand, so it is clear they are expecting the corporate sector to take up the slack.

If corporate investment has not picked up despite tax cuts or aggressive capex spending over the last four years, there has to be the expectation that the income tax cuts would increase consumption demand, which would require an increase in investment, thereby setting a virtuous cycle of growth begetting growth. Yet again, we are back to income tax cuts. Does putting all your eggs in one basket make sense when things are not going your way? And yet, this is what the government seems to have done. It’s a one way gamble.

Rohit Azad teaches economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Indranil Chowdhury teaches economics at PGDAV college, DU

Published – February 05, 2025 08:30 am IST