Various urban elements, from construction materials to transportation fuels, create ‘hot’ cities, amplifying temperatures by several degrees compared to rural areas. The Indian Meteorological Department has warned of a scorching summer this year with more than the usual number of heatwave days. Some places are likely to face maximum temperatures crossing 40 degrees Celsius. In response, effective strategies for heat management are imperative, necessitating a multifaceted approach encompassing sustainable urban planning, infrastructure development, and public engagement. One crucial aspect gaining traction is the integration of kindness-centric designs aimed at cooling our cities and prioritising human comfort and well-being.

As the scorching summer heat has become an ever-present challenge in most Indian metropolitan cities, the urgency to design user-centric designs for heat resilience has never been greater. Modern strategies such as green infrastructure, building regulations, water management, public transportation and sustainable design practices are pivotal in reshaping our cities into oases of comfort and well-being. We can forge cooler environments that prioritise users’ comfort and satisfaction by drawing inspiration from our traditional practices and merging these with contemporary strategies.

Vertical gardens

Green infrastructure emerges as a powerful tool in combating urban heat islands, creating cooler microclimates, and fostering communities. Planting trees along the streets and integrating green-blue corridors within urban planning are tangible steps towards this goal. These initiatives mitigate urban heat and cultivate a sense of community and harmony with nature. Allocating budgets for urban schemes and enhancing technical expertise in local governance is vital for implementing effective climate strategies.

Gardens by the Bay in Singapore.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/iStockphoto

An example is Singapore’s Gardens by the Bay, a vast green space integrated with sustainable technology to cool the surrounding area. The Gardens by the Bay features Supertrees, towering vertical gardens that provide shade, harness solar energy, and collect rainwater, showcasing an innovative approach to combating heat while promoting biodiversity and creating a powerful social node.

Pushkarni stepwell in Hampi, Karnataka.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Recharging groundwater

Waterbodies act as natural heat sinks, while contributing significantly to groundwater replenishment. In India, the tradition of baolis, ancient stepwells, offers a timeless solution for summer relief. These architectural wonders not only recharge groundwater but also provide natural cooling during summers, showcasing a sustainable approach deeply ingrained in Indian heritage. Additionally, serving as social centres, baolis historically brought communities together, fostering connections and providing respite from the heat in more ways than one. Through rainwater harvesting, the creation of artificial ponds, and the rejuvenation of existing waterbodies, we can help create cooling zones within neighbourhoods.

At a masterplanning level, the allocation of surface area for built zones and open spaces should be based on the water’s percolation potential, aiming to maximise local water conservation efforts. Drawing inspiration from traditional Indian baolis, modern infrastructure can incorporate water features and vegetation as heat sinks in urban areas.

Beautification of the Rajokri waterbody in New Delhi.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

The rejuvenation of Rajokri waterbody in New Delhi is a remarkable example of effective water management. The lake was revived through the scientific wetland system, improving water quality, promoting groundwater recharge, and acting as a buffer against flooding. The project also included landscaping for public gatherings, creating green play areas, and constructing rain gardens to prevent flooding and enhance water availability for local needs.

Another important city-level change that must be implemented is the development of public transportation networks. Efficient urban planning can reduce the number of private vehicles on the road. This decreases traffic congestion and lowers vehicle heat emissions, improving air quality and reducing urban temperatures. By promoting shared infrastructure and encouraging active modes of transportation, we can combat heat and nurture a sense of community and connectivity among residents.

Bus Rapid Transit system in Curitiba, Brazil.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Curitiba, Brazil, is a model city known for its Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system, which reduces the reliance on private vehicles and mitigates heat-related issues. The system’s efficient design, dedicated lanes, and frequent service reduce heat emissions and encourage public transport usage, contributing to a cooler and more sustainable urban environment at the neighbourhood level.

Public facilities

One of the most iconic and thoughtful design elements in traditional Indian towns is the ‘pyau’, or drinking water utility. Nestled in busy streets, religious sites, and public buildings, these humble structures not only quench thirst but also offer respite from the relentless heat. However, their presence has dwindled in contemporary urban landscapes. Reviving such amenities aligns with the ethos of kindness-centric design, emphasising the fusion of shade, rest, and water as essential elements for heat stress relief. As part of Swachh Bharat Mission, the construction of toilets along large public building boundaries, presents an opportunity to expand this concept further. Instead of mere functional blocks, envisioning these spaces as small verandahs with drinking water facilities can transform them into welcoming havens for weary city dwellers also working as gathering points within the area, promoting social interaction and cohesion.

The shift towards environmentally conscious building regulations is paramount. Prioritising heat-resilient materials, natural ventilation, and shading techniques while curbing untreated glass can significantly reduce building heat gain. Orienting buildings correctly, allowing natural ventilation, and analysing building design at a neighbourhood level will all help reduce temperatures substantially.

Automated shading systems

At an individual level, conscious steps towards heat resilience can help achieve larger-scale initiatives. Traditional Indian architecture features chajjas (projecting eaves) and jaalis (perforated screens) that promote natural ventilation and shade, reducing heat gain in buildings. Incorporating balconies and terraces eases the transition between indoors and outdoors while protecting the interiors from direct heat gain. Modern buildings can emulate these features in innovative ways to enhance heat resilience. One effective way is to opt for modern facade systems.

Sun-tracking systems

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Dynamic elements, such as sun-tracking panels or automated shading systems, take facade design to the next level by responding to environmental conditions in real-time. These systems adjust the angle or position of louvres, shades, or panels based on factors like sunlight intensity, wind direction, and outdoor temperature. Shading devices, such as awnings, canopies, and fins, are another integral part of modern facade systems. These devices are designed to cast shadows and provide shade to building surfaces, windows, and outdoor spaces. Ensuring sufficient shading around the properties helps avoid external heat generated by air conditioning units.

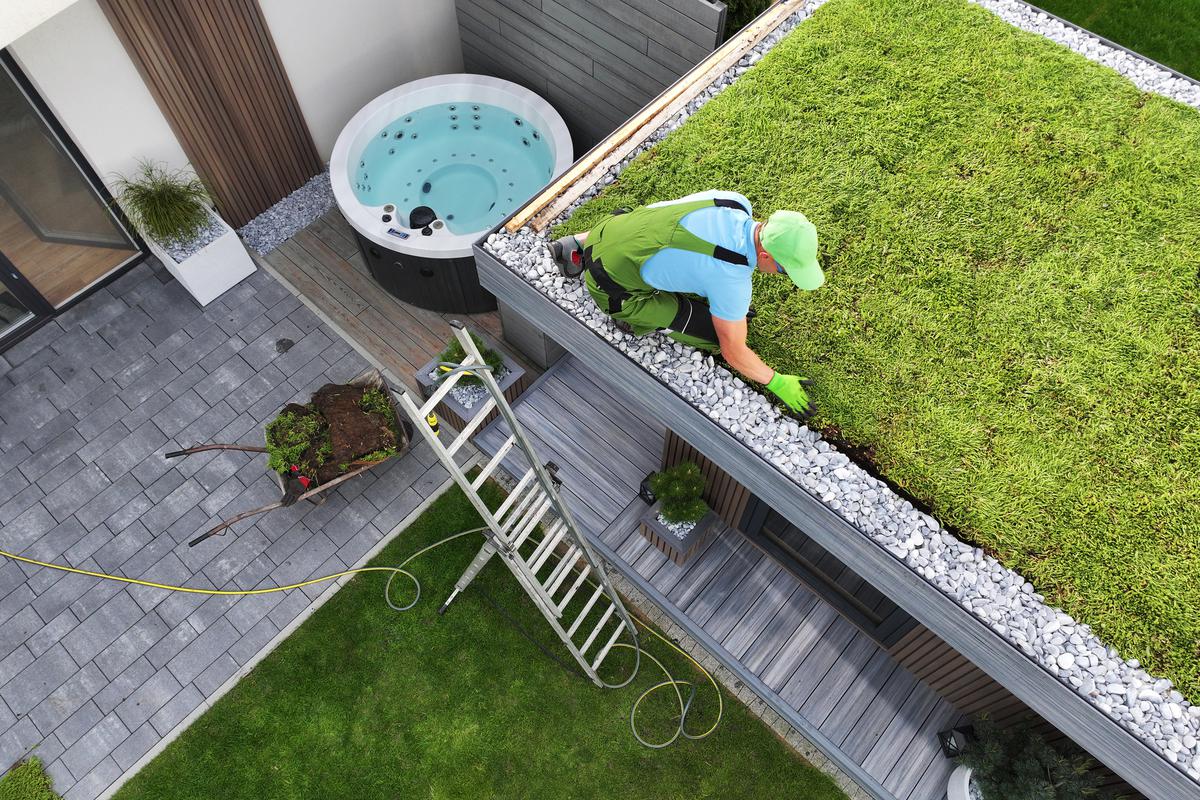

Installing green roofs.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Another impactful measure is to consider installing green roofs, which provide insulation and reduce stormwater runoff, contributing to significantly lower indoor temperatures. Individuals can also contribute by incorporating small water features or drinking water facilities at private boundary walls, offering a refreshing respite and creating a more compassionate urban environment.

The writer is Partner at team3.