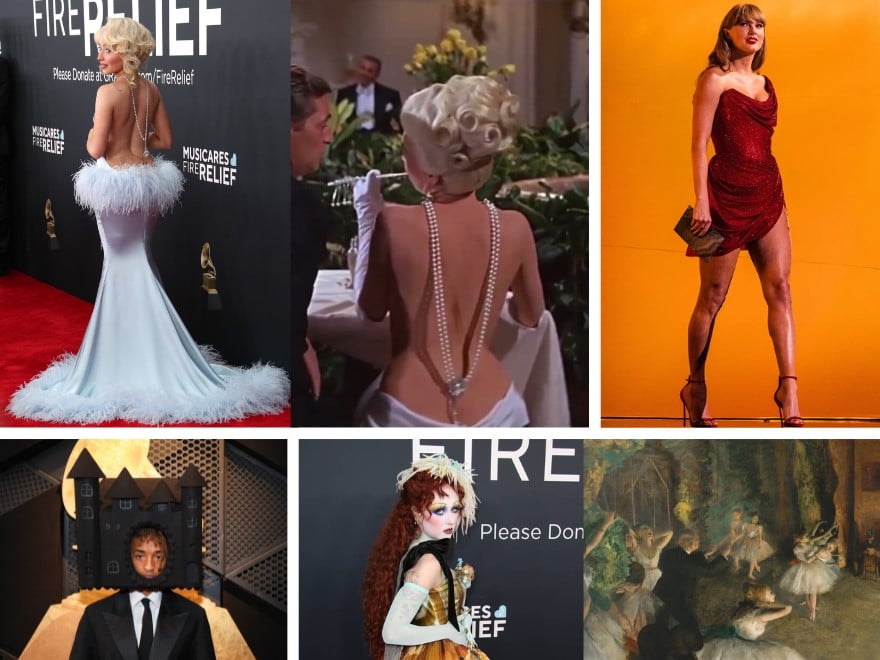

The quiet chaos of food obsession and unrealistic body standards that runs rampant in present-day society

KARACHI:

If you’ve ever found yourself in an overly tangled mess of food-related thoughts and habits, you might be wondering if your behaviours land you in the confines of an eating disorder or the milder disordered eating. Think of it like this: if an eating disorder is the loud, headline-grabbing sibling, disordered eating is the more subtle, but still disruptive, younger one. While eating disorders are classified as DSM-5 mental health conditions, disordered eating is more of a behavioural issue, albeit one that can throw your life into chaos if left unchecked.

It sits on a spectrum between typical eating patterns and a full-blown eating disorder, sometimes borrowing behaviours like restrictive eating, compulsive overeating, or unpredictable eating patterns, but at a lower frequency. It’s also particularly rampant among younger generations who have jumped from diet to diet faster than they can swipe to the next TikTok video. From skipping meals to bingeing on comfort food, avoiding entire food groups, or diving headfirst into fad diets (remember Keto? I’m not sure I can ever look at an avocado the same way), these patterns have become almost normalised.

The number obsession

The journey down the disordered eating rabbit hole can begin innocuously enough—maybe a trainer or a seemingly innocent Google search on “how to lose weight fast” recommends a daily intake of 1200 calories. Before you know it, you’re manically logging every calorie in one of those tracker apps, feeling equal parts guilt and desperation when you slightly overshoot your goal and see the dreaded number in red. Of course, because you’re determined to beat the app at its own game, those 1200 calories will gradually shrink to 1000, then 800, and suddenly, you’re surviving on less than what’s required for basic human functioning. But hey, that lower number on the scale makes it all feel worth it, right?

Except disordered eating doesn’t exactly play fair. One day, you might decide to “treat” yourself, only to spiral into a month-long binge that leaves you feeling not only sick to your stomach but sick of yourself. Even if you manage to pull yourself out of the binge, you’ll likely wind up right where you began, glued to your calorie-counting app. It’s not just about losing weight, though. Someone with the leanest, fittest body can still stare in the mirror and pick apart what they see. The driving force is different for everyone, but the path is eerily similar.

Running on empty

Disordered eating doesn’t limit itself to food either—it’ll creep into your exercise habits too. A single gym session won’t feel like enough, so you’ll add another, then maybe some pilates or tennis for good measure. Before you know it, you’re exercising like an athlete but eating like a bird, only to wind up with splitting headaches and no energy to show for it.

Then there’s the social toll: avoiding gatherings because the thought of wearing clothes you don’t feel comfortable in is just too much to bear. And let’s not forget the binge eating, which often brings a side dish of shame along for the ride. This could mean avoiding eating in front of others at the dinner table only to snacking an unfortunate amount in the privacy of your bedroom at night.

So, why are some more prone to falling into this cycle than others? Psychotherapist Dr Humaira Affan points to a lack of control in other areas of life as a key factor. “People who can’t control their environment, emotions, or relationships often turn to controlling their food and body as a way to cope. They tend to have low self-esteem and worry they won’t be accepted unless they look a certain way,” she explains. Can anyone really blame them, given the unrealistic beauty standards plastered all over social media?

Dr Humaira also sheds light on how these tendencies can take root in childhood or adolescence. “In my experience, eating disorders often develop in children who have been shamed or criticised for their appearance or eating habits by parents from a young age,” she says. The controlling behaviour of a parent, whether it’s about diet or otherwise, can trigger these issues, so sometimes, it’s a form of rebellion. We’ve all heard those comments from mothers (or the ever-helpful aunties and uncles), “You’ll never get any proposals looking like that,” or “You’re not going to look good in your clothes.”

Balance beyond the scale

When it comes to turning the tide on disordered eating, clinical nutritionist Dr Azmat Alibhai emphasises the importance of balance. “Establishing regular meals is crucial— meals with a mix of carbohydrates, proteins, fats, and plenty of fruits and vegetables,” she advises.

Now you may be wondering how to incorporate carbohydrates and fats if you’re supposed to be eating healthy. After all, there was a time they were on the “do not eat under any circumstances” list of every health freak out there. Dr Azmat says that’s not true at all. “Carbs and fats aren’t the villains they’re made out to be. The body needs them to function. The role of a nutritionist is to educate and explain how not all carbs and fats are bad for you so that the patient is no longer anxious at the thought of them.”

Some advice for those married to their calorie tracker app or weighing scale: get a divorce. “Practice mindful eating, paying attention to your hunger and fullness cues, and try to enjoy food without judgment,” says the American Board-certified nutritionist. She emphasises that if the body is not nourished it’ll lose focus, which opens the gates to intrusive thoughts and heightened emotions.

On the psychological front, Dr Humaira underscores the slow but essential process of building self-esteem. “Self-worth isn’t about how much you weigh or what you look like. It’s about who you are emotionally and mentally,” she reminds us. And while disordered eating is often milder than a full-blown eating disorder, it’s not without risks. Left unchecked, it can escalate, requiring not just therapy but, in some cases, medication. “There’s a lot of hopelessness and helplessness during recovery, which rigorous psychotherapy can help with,” she says. “A team approach, including an on-board nutritionist, is crucial to simultaneously tackling both the psychological and physical aspects.”

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.