It was a simple Hornby model train set, and the track formations he could make with it, that sparked Charles Correa’s interest in architecture as a child. This is one of the first things we discover at ‘Conversations with Charles Correa: A Critical Review on Six Decades of Practice’, held last month in Mumbai, when author Mustansir Dalvi launched the first biography on the visionary modernist architect. The two-day conference, in its third edition, had scholars and professionals discussing different facets of his work, ranging from his ideas on urbanism to his writings on cities. And, of course, his buildings — from Correa’s Gandhi Ashram, which visual artist Kaiwan Shaban once referred to as “one of the finest examples of humility in architecture”, to the multiplicity of Jawahar Kala Kendra.

Architect Charles Correa

Correa didn’t see architecture as just designing modern buildings. He wanted his work to bring about positive change. “He was very much a modernist, not just stylistically, but because he believed modernism helped one uncover what was actually required,” recalls his daughter, architect Nondita Correa Mehrotra. “So, there was no style attached to it, but it allowed everyone to have a place in society; unlike traditionalism which is guided by a series of unknown rules and regulations.”

Rural folk migrating to metropolises, for instance, was a focus for Correa. “He always stressed how we can’t turn them back, and one of his favourite examples was the BEST buses in Bombay being an equaliser — it brings together everyone from the upper castes to the Dalits under the same roof. This mode of public transport can very quickly undo centuries of caste thinking,” says Mehrotra.

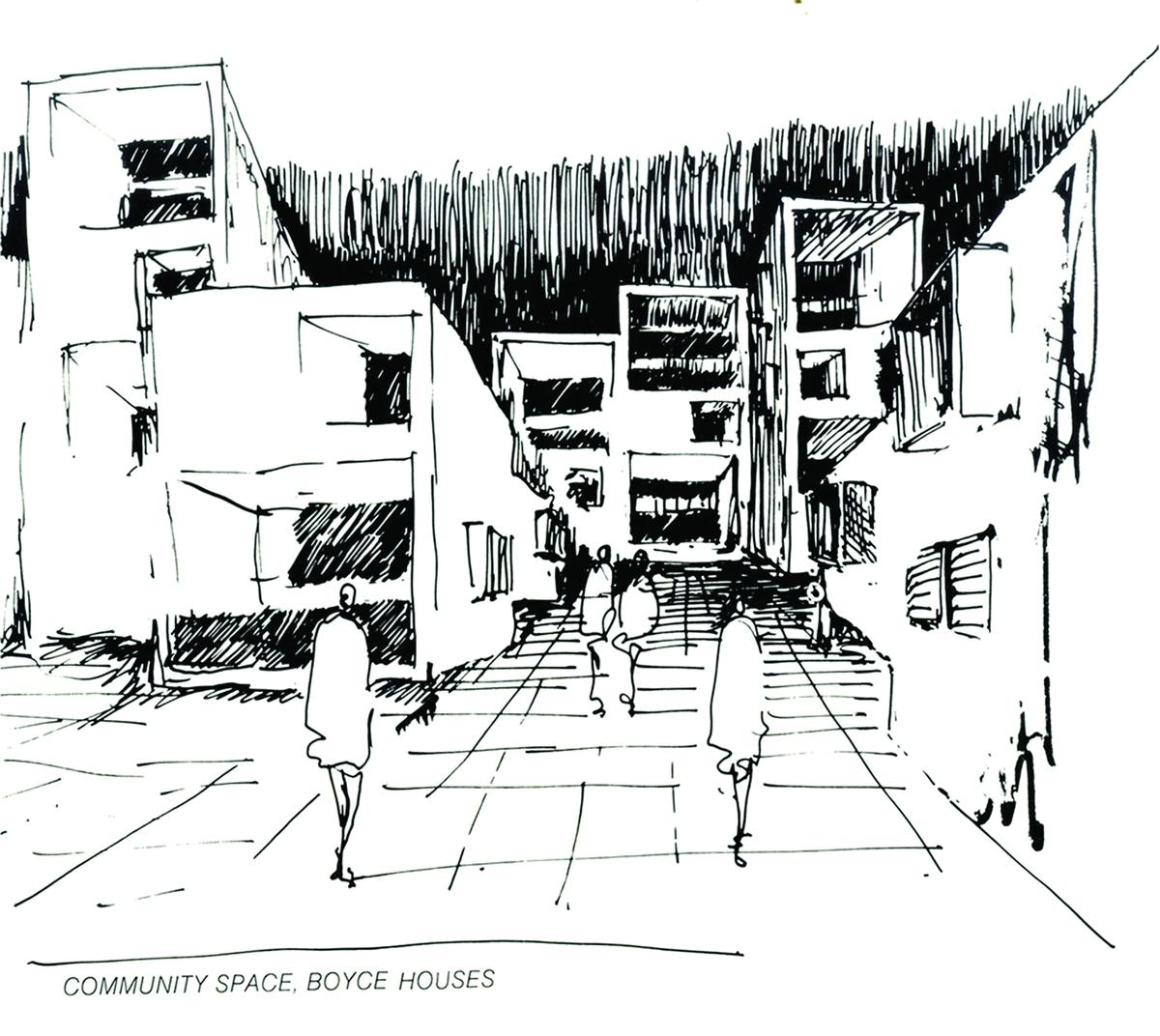

Boyce House

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Charles Correa Foundation

Hudco housing

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Charles Correa Foundation

The Magazine asked a few experts who spoke at the event, or have been admirers of his work, to share why the architect is relevant today, and what Generation Now can learn from him.

Ranjit Hoskote

Poet and cultural theorist

“Charles, for me, was many things beyond an architect — a thinker, a curator, an urban designer — someone who had a much larger social vision and commitment, bringing in a new spirit of congregation. He continues to be relevant for architects today. He saw an architect as a part of the larger plan to build a new nation. It’s important for young architects to not see themselves as specialists, who simply do what corporate clients ask of them,” Hoskote emphasises. “‘What’s the common good, what kind of future is optimal?’ These are the questions they should ask, especially between the current climate crises and runaway urbanisation. Charles always stressed how a building is part of a precinct, which is part of a neighbourhood, which is part of a city, and those relationships need to be maintained through the detailing and scale. The lack of planning, attention to individuals and community space due to the rapid pace of urbanisation saddened him.”

Ranjit Hoskote

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

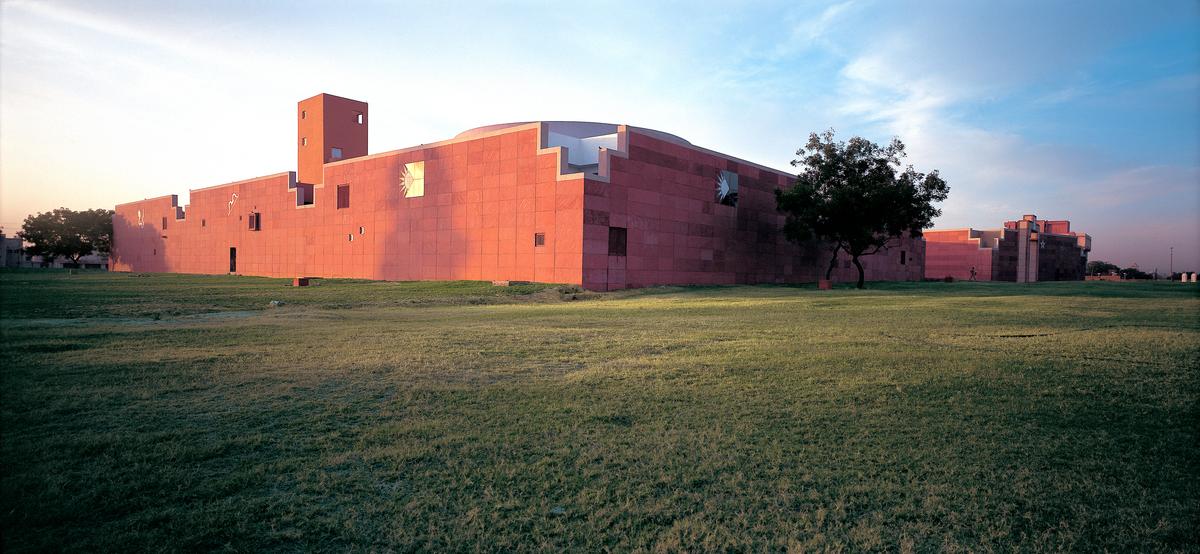

Of note: “The Jawahar Kala Kendra in Jaipur is responsive to the nature of the site, and becomes a labyrinth of surprises through a series of deflections. The Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics in Pune brings together things that were important to him as a student [erasing the distinction between the arts and the sciences]. He embodies that in his choices of materials and motifs.”

Jawahar Kala Kendra

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Charles Correa Foundation

Rajnish Wattas

Former principal of Chandigarh College of Architecture

Wattas, who has penned a large number of writings on Correa, recalls inviting him for lectures at the university. “He was a star speaker, and we’d have a rush of students who’d come to hear him talk,” he reminisces. “He triggered new ways of architectural thinking in the context of India, many parts of which were shaped after Independence by architects from overseas such as Le Corbusier for Chandigarh and Louis Kahn in Ahmedabad. Charles imbibed a lot from Corbusier, but not with blinkers — instead inventing and contextualising modernity to the India sensibility and climatic conditions. He emphasised on courtyards and open-to-sky dwellings instead of towering blocks. Even in Kanchanjunga, you’ll find large terraces within a high rise.”

Rajnish Wattas

| Photo Credit:

Akhilesh Kumar

Wattas bemoans the urban skyline in the country now, mere “C-grade versions of Hong Kong or the Middle East. There is no echo of our art and culture, or relevance to the topography. It’s not that Charles was against modern materials like glass — he thought it beautiful, bringing in light and helping blend the inside with the outdoors. The issue was the creativity of its usage”.

Of note: “Jeevan Bharti, a two-wing, 98-metre-long pergola in Connaught Place in New Delhi has a dizzying complex network of glass grids with an earthy Indian exposed brick form alongside it.”

Jeevan Bharti

| Photo Credit:

Sandeep Saxena

Ashiesh Shah

Architect

There’s always something to take away from Correa’s designs, believes Shah, whose first memory of the late architect was the awe he felt seeing the high-rise Kanchanjunga being built. “We’d never seen such a sculptural structure come up so quickly in South Bombay,” he recalls. “Growing up in the ’90s, we all studied his work. But that was a very different era; architecture was not the glamorous entity that it’s become today. India was also in a different position: we were reeling from a recession. If you were building anything, it needed to have a strong purpose, and Charles had very strong thoughts on urban planning.”

Ashiesh Shah

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

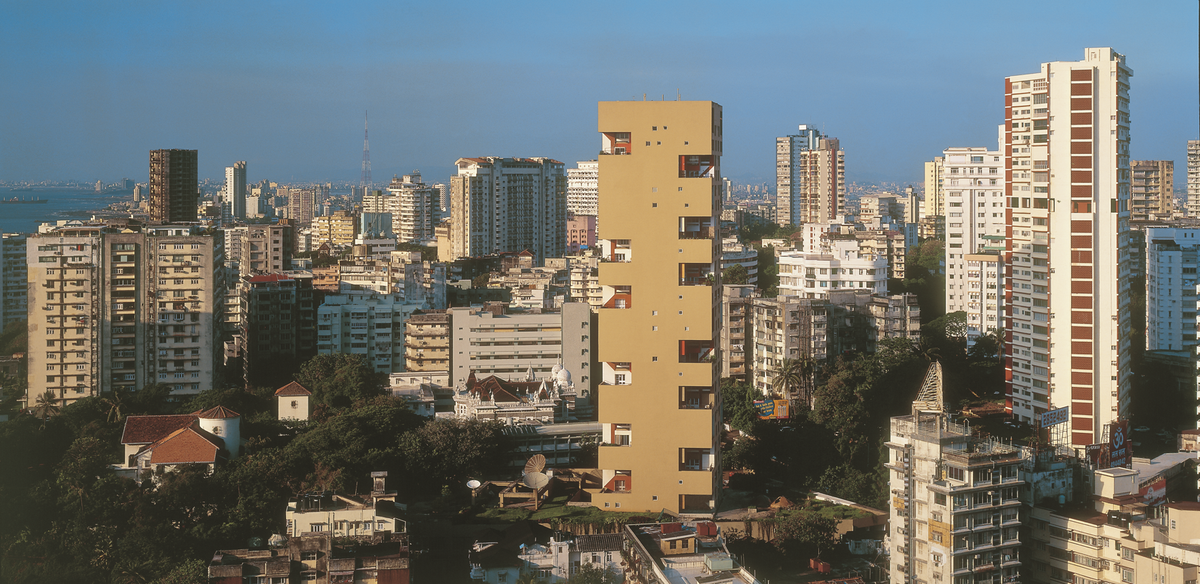

Of note: “Buildings like Kanchanjunga are a lesson in energy conservation today. There was no air conditioning back then, and Correa was building for the environment [with double-height spaces, terraces, and plenty of cross-ventilation]. So there’s a lesson we can carry with us today.”

Kanchanjunga

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Charles Correa Foundation

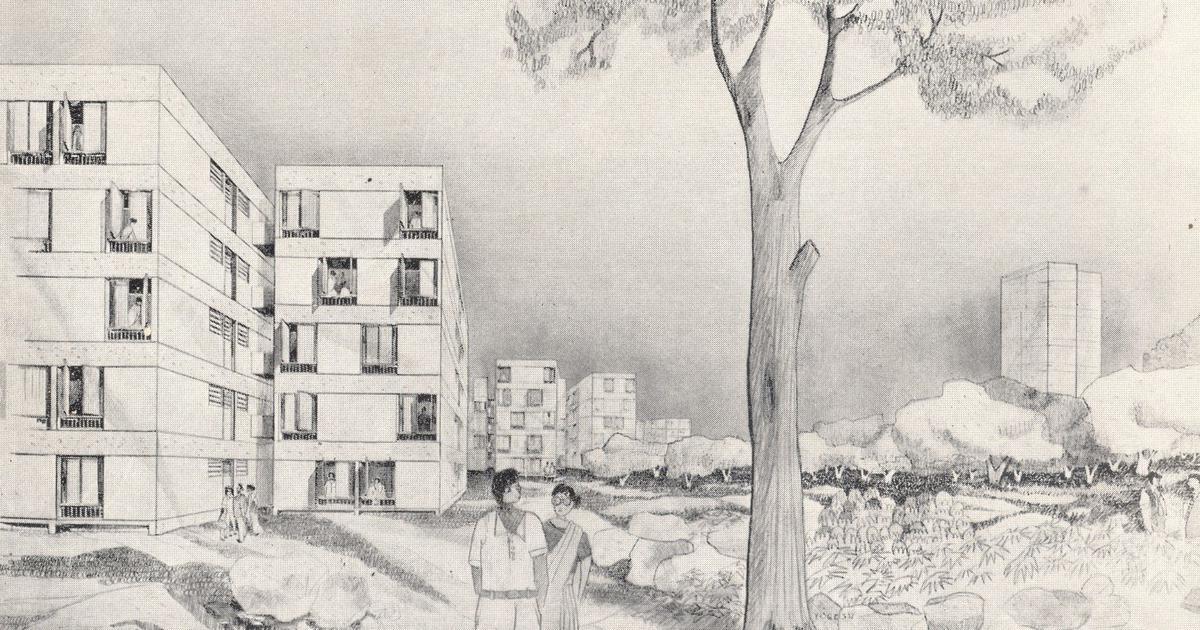

View from an LIC Colony

Lovely Villa, a film by architect and filmmaker Rohan Shivkumar, poetically captures the intimacies of architecture, emotion, and everyday life in the LIC Colony he grew up in. “In the 70s, my parents invested in an LIC ‘Own Your Home’ policy. They received a brochure for the opportunity to buy an apartment in Charles Correa’s colony,” he shares, recalling how, slowly, other family members moved there too, appreciating its design and spatial quality. “One of my uncles was an architect, and once pointed out Kanchanjunga remarking how the same architect designed our colony, too. I suppose that’s when I realised we were living in something special.” He recalls how life in the LIC Colony introduced everyone to a value system of modern India. “It had everything from small-sized apartments to large four-bedroom houses, and were loosely designed together, not policed by any social boundaries, which, I think, are more stark today. It was a new and modern way of living.”

A skecth of the colony

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Charles Correa Foundation

Published – November 01, 2024 01:03 pm IST